Earlier this year, I traveled into the North-Eastern Amazon in the Brazilian state of Maranhão to do two stories for the LA Times – One on deforestation, and one on modern-day slavery.

Los Angeles Times – Brazil workers exploited as modern-day Amazon slaves

Los Angeles Times – Amazon in danger as Brazil moves forward with bill, critics say

What I found, in short – and which hopefully is communicated by the photo essay below – is that commodity-based development is a lot less pretty up close in person.

Despite the obvious facts that mining is literally just ripping the hard bits out of the Earth’s surface, and that the cattle industry requires vast swathes of the forest to be cleared away, you also cannot help running across exploitation of labor and invasions of protected areas. If you peek behind Brazil’s boom in Maranhão, you often find bad news.

But today there is some good news. Greenpeace has announced that pig iron manufacturers in the state have agreed to cut slave labor, deforestation, and indigenous land invasions out of their supply chains. At the same time I was publishing the reports, Greenpeace – which at times provided me logistical support – was putting pressure on the US steel companies that buy that pig iron. If everyone makes good on the agreement, there’s no reason local conditions couldn’t improve without causing much market distortion.

Below are the photos (all taken by me, decidedly an amateur), that hopefully give a sense of what the ugly side of development in the region feels like.

The first set are taken from a plane.

A mix of deforested land, native growth (the dark green stuff, center-right), and ‘re-forested’ areas. The latter is usually 100% eucalyptus and is identifiable by tall, uniform rows of trees (bottom).

Deforested land. Most of the state looks like this, and is used for cattle grazing.

The railway which takes iron ore and charcoal from the heart of the jungle to the port, where which it is shipped abroad. More on this one below.

A charcoal production facility, where wood is burned into charcoal. Like deforestation, this process is one that often relies on slave-like labor. We had no idea if this one was legal or not.

Father and son, talking about their experiences. Both have found themselves in working slave-like conditions in this part of Brazil.

A truck breaks down as it is hauling away (looks like natural) wood

As we drove into a camp where one man claimed he had worked as a slave producing charcoal, the sign was not so welcoming. Though it reads “Join in solidarity, love nature”, it is riddled with bullet holes.

One of the coal pits where the man said he had worked. He says he passed out from heat exhaustion and has since lost control of his legs. The owners refused to transport him out for medical treatment.

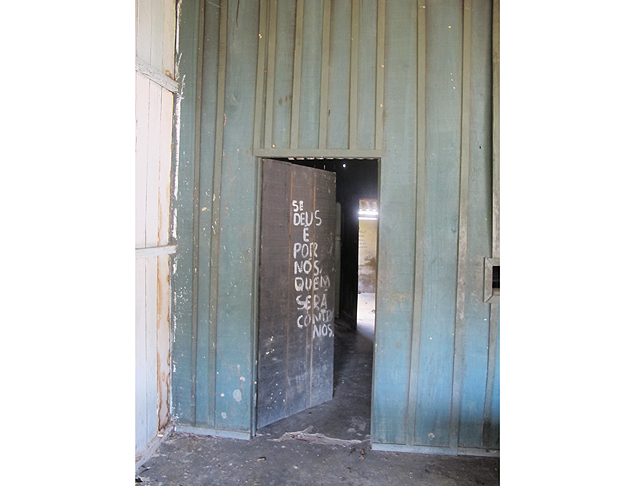

The previous three are living quarters

The previous three are living quarters

A woman wades into a lake which has been polluted by the train tracks on which iron ore and charcoal are shipped out of the area. Earlier this week, the Brazilian government denied Vale the right to double this track, on environmental grounds.

A woman wades into a lake which has been polluted by the train tracks on which iron ore and charcoal are shipped out of the area. Earlier this week, the Brazilian government denied Vale the right to double this track, on environmental grounds.

Gil Dasio Meirelles, the protagonist of my LA Times story. The sign reads: “Keep your eyes open to avoid becoming a slave.”

Los Angeles Times – Brazil workers exploited as modern-day Amazon slaves

Los Angeles Times – Amazon in danger as Brazil moves forward with bill, critics say