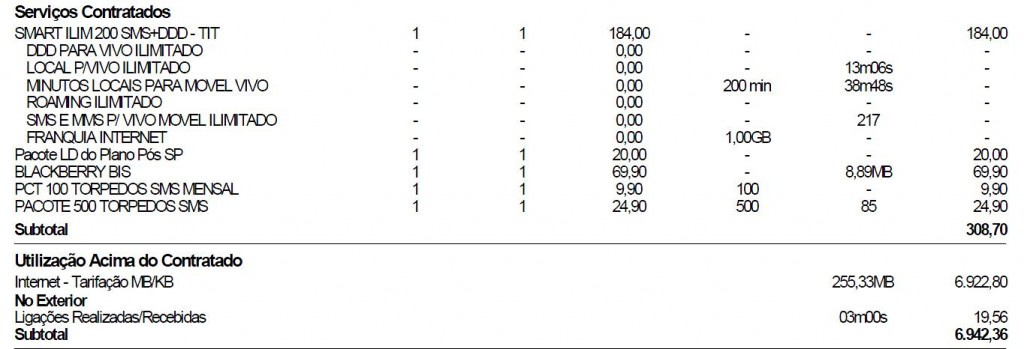

A lack of consumer protections means big profits for companies. A Vivo employee, for example, admitted to me they make it as hard as possible to contest mistakes on a bill. But those really suffering as a result aren’t people like me (despite the 6,800 reais mistake in my phone bill yesterday, above) but poor Brazilians.

Note – Update included at bottom of post

I had already given some thought to adding to Helen Joyce’s excellent post at The Economist on the trials of being a TIM customer in Brazil, and not (only) because she seemed to get bizarrely obvious special treatment as a result.

It was because I think in some ways there is something more sinister going on here than just the ‘custo Brasil’. There seems to be an intentional attempt to profit nicely by making customer service issues extremely difficult to resolve, and TIM is far from the only guilty party on this one.

At least, that’s what my own Vivo Saga had been telling me for months. And then yesterday, a new chapter was opened which made me laugh uncontrollably between shrieks of terror. I discovered that Vivo had unceremoniously instructed my bank to transfer 7,159.86 reais to them.

That’s right. Instead of the normal 300-400 reais I pay, this time it was the equivalent of $3,500 US dollars for my monthly cell phone bill, and it was just going to disappear from my bank like that. Luckily for me, I don’t even have that kind of money in my Brazilian account, so it was stopped.

They are supposedly in the process of cleaning this up. But even if they do, one has to ask – if a consumer made a payments mistake to the tune of seven thousand reais, do you think there might be some consequences for him?

Unfortunately, my saga seems to me more evidence of how, in one of the world’s most unequal countries, corporations so easily get away with stepping all over the little people (and neither Helen or I, of course, are the actual little people).

The quick story:

I’ve had a Vivo Blackberry post-payment plan for a few years. And to use it abroad, I always paid a 180 rs fee to enable unlimited small-volume international data use for three months at a time. It wasn’t exactly cheap as it meant my monthly bill was 300-450 reais, but it was essential for my job.

But in January something must have changed, since my bill came in at 900. Seeing this was a big problem, I took a morning off work and went into the local Vivo shop.

“Oh, for any bill issues, we can’t help you, as we have no phones ourselves, but feel free to use the phones over there in the corner to talk to a someone,” he said.

What? The customer service representatives at the Vivo store don’t have access to the system? They don’t have phones?

I went over to the phones, where I spent over over an hour being transferred back and forth before someone would ultimately just hang up on me. Over and over. I think they must pretend this is a dropped call when you are on your cellphone, but I wasn’t. I was on their own fixed line.

The nice man at the desk didn’t know how to help me. That’s the only way, he said.

“Hrm,” I said. “They can’t find the person to help me. You here don’t have access to the system. You don’t even have phones. Don’t you think this is all set up on purpose to make it almost impossible for the customer to contest a mistake on the bill?”

“I think it’s pretty obvious that’s what it must be,” he said, shrugging with genuine sympathy. “It certainly works out that way for almost everyone.”

I eventually did get that January charge brought down to 300 reais, through an endless combination of in-person visits, phone calls, waiting, and whining obnoxiously on Twitter. How exactly is not interesting. But what is worth noting is that it was more trouble than it was worth. If I was a self-interested rational economic actor, I would have just let them have the r$600.

It was only through a combination of rage and curiosity that I saw this through to the end. In the process, I wasted so much time that I easily lost out on much more than r$600 in extra work I could have done.

But I am not normal here, of course. I earn much more than the average Brazilian, who takes home about 1,300 reais monthly. I also have a blog at Folha de S.Paulo and can make a stink if need be. Who really gets screwed due to a lack of consumer protections, quite obviously, is the new middle class, the working poor, navigating these systems for the first time and without the time or money to deal with being taken advantage of. There are many other ways this works, but first, briefly, back to me crying about my own problems.

After I resolved my January bill, I went back into the shop and made sure I could re-activate my old international unlimited data plan. They said yes. Then, on the way to the airport before a trip abroad, I called again to confirm it would be 180 reais, unlimited. They said yes.

Then yesterday, I saw an automatic debit transfer of over 7,000 reais was in motion for using my data plan abroad. I called, and I’m currently waiting (five business days…) for them to look into it and get back to me.

But imagine how much money that is for an average Brazilian. For a minimum-wage worker, the mistake in my phone bill is equivalent to approximately what they make in a year. And what does Vivo have to lose by constantly over-charging everyone? Worth a try.

At the risk of sounding reductionist, this is a country in which a small few have long profited off of the backs of many, often to a much greater extent than is true in many other countries. An overly simplistic narrative might be that the exploited worker is now being replaced by the exploited consumer.

Another obvious way this works is that banks and retailers push consumers into taking on debt at usurious rates for their purchases, without explaining what the actual interest burden will be (often over 100%). I know I have been shoved in this direction. I can’t imagine this should be legal.

As this analysis in Super Interessante correctly points out, we’re not just dealing with the ‘custo Brasil’ but also the ‘lucro Brasil’ – or the ‘Brazil profit.’

Here’s hoping Brazilians will be able to successfully demand their rights in the consumer marketplace, the way they previously did in the workplace.

UPDATE: May 8 – Vivo contacted me immediately about the post, asking for my number so they could look into the issue. I politely declined to share it with them and receive special treatment (for now, at least…) and instead asked to be able to submit a set of questions about their practices and the market more generally.

After all, I was not trying to single out Vivo as especially bad (As Helen’s post points out, they receive less complaints than any other company), and certainly not to just get my own problem solved. The normal respondents on the helpline said they’d be back to me in five days, so I’ll wait to see how that goes.

The more interesting question for this blog is how the companies relate to consumers in Brazil, whether I am right about their strategies, and how things can improve. So, if they agree to the interview (and I hope they do), some potential questions:

1. Why don’t service agents in Vivo shops have phones?

2. Why can’t they help with complaints?

3. If a customer makes a small mistake, they are punished dearly. If the company makes a huge mistake, there is no automatic penalty. Why not?

4. How has hanging up on customers come to seem like company policy?

Etc., Etc. If you have any questions of your own, feel free to send them in.