Artists from Latin America and the world come together in Porto Alegre for a Bienal still named after Mercosul, the stalled regional integration project. Claire Rigby reports on the transformations on offer there.

By Claire Rigby

Moving, evocative, mysterious, provocative: not all great art supplies these sensations, but when it does, it has the power to leave your brain smouldering with new ideas for days. Taken in sufficient doses, that sense of connections being made, and new understandings taking shape via artworks, can even last a lifetime. It’s transformational – it’s the point of art, and it’s art’s sacred calling.

Last week’s opening weekend at the Bienal do Mercosul Porto Alegre, in the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul, was suffused with interesting, important ideas transmitted via a collection of artworks chosen with precision, all woven into in an interconnected web by the thoughtful young curator Sofía Hernández Chong Cuy.

Entitled ‘Weather Permitting’ (‘Se o clima for favorável’, in Portuguese), this biennale is a tapestry of big, poetic ideas around shapes and masses underground and in the atmosphere, and concepts related to time travel, space and climate – climate in a physical sense, rather than in the concept’s ecologically-charged, more common present-day guise. The exhibition takes place in a row of three adjacent museums in downtown Porto Alegre, and in an old gasworks building, the Usina do Gasômetro, repurposed as a cultural centre. It also takes place in a monthly series of discussions-slash-expeditions to a nearby island and former prison, Ilha do Presídio.

This is the Bienal do Mercosul’s 9th edition – the first took place in 1997, when Mercosul, the Southern Cone economic bloc founded in 1991 and modeled on the EEC, still seemed like it might become a meaningful regional force. As one of two biennales in Brazil (the other is in São Paulo), the Bienal’s setting in the breezy, creative city of Porto Alegre has come to mean more to it than its connection to the failed South American political alliance.

In the grandest of the three main venues, Santander Cultural, a giant, hyper-realistic ceramic squid by the Peruvian artist David Zink Yi lays splatted on the floor, dead, its ink oozing around it (see main image, top). In the main atrium of the next-door building, Memorial do Rio Grande do Sul, a thick carpet of powdered rust has been laid down by the always compelling Cinthia Marcelle, aided by the reckless intervention of nocturnal insects, scurrying minute tracks into it, night by night. And in the adjacent MARG (Museu de Arte de Rio Grande do Sul), a suspended 6m-long satellite made of finely meshed wire hangers and ham radio equipment looks almost invisible until you are right beneath it, staring up. It was constructed by the artistic duo Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla with the intention, in part, of making contact – real contact, by radio – with the International Space Station as it spins through the atmosphere, passing over every 90 minutes, 250 miles overhead.

The opening weekend brought the static artworks together with a series of performance pieces. On the grassed-over roof of the gasworks, the artist David Medalla gave a performance that wove dance, poetry, clouds of balloons and the setting sun into a joyful happening that left parts of the audience, thick with artists, gallerists and a Brazilian and international art crowd, wreathed in smiles and tears.

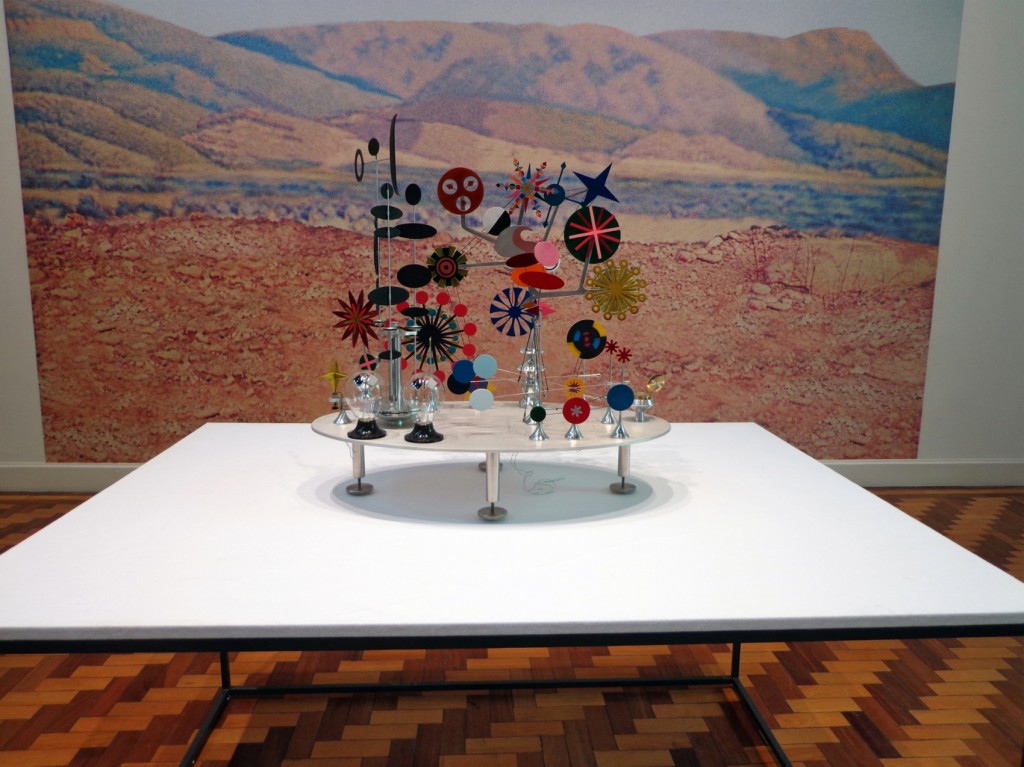

The work of Medalla, who was a leading member of the 1960s avant garde and a co-founder of London’s Signal Gallery in 1964, has been gathering new interest and recognition in recent years, not least thanks to his association with São Paulo’s Baró Galeria, and he was one of only a handful of artists to have more than one work in the Bienal, including a specially commissioned version of his 1960s Bubble Machine, a cluster of perspex towers from which dense, featherlight foam sculptures are emitted slowly, minutely, and around the clock. Earlier that afternoon, in a techno-music/psychogeographic sound performance, the young Lebanese artist Tarek Atoui worked a radio signal from the Ilha do Presídio island, out in the estuary, into a hypnotic and discomforting soundscape, shaping the sounds with his hands using a theramin-like contraption on his mixing desk.

You can see a short film here, of the curator, Sofía Hernández Chong Cuy, pointing out the prison island along with the rest of the Bienal’s venues as she flies over Porto Alegre in a helicopter (in Spanish). In person, Hernández, who lives in New York, is a fascinating speaker, expressing her ideas with precision, artistry and effortless depth.

This is the curator speaking off the cuff as she smoked a cigarette down by the river on the Saturday afternoon of the opening weekend, when questioned about the ideas that influenced her choices of themes for the Bienal: “Understanding the weather is also a way of understanding how observation works – understanding the importance of contemplation, and of observing something.”

Some new people turn up at the riverbank, in sight of the gasworks, where another performance is taking place. Hernández gets a light for her cigarette, greets the new arrivals, and picks up her train of thought again. “When I say ‘observe’ and then I move to ‘contemplation’, it’s because they’re related: they are about looking inside – a constant movement between what you are looking at and what you know. Understanding the reality, and co-existing better. It’s about losing yourself, but also understanding yourself more.”

- The Bienal is on until 10 November, and if a trip to Porto Alegre is possible, it’s highly recommended. If not, some of the texts associated with the Bienal are available for download here. An e-book of essays, The Cloud, and one of the artworks, an album of songs by the Mexican artist Mario Garcia Torres, commissioned for the Bienal, can be downloaded track by track at the same page.

- Listen to the sound of mud bubbling and popping in a vat, part of ‘Mud Muse’, a sound and mud sculpture originally made in 1969 by Robert Rauschenberg.

All photos Ⓒ Claire Rigby.