Above, a young member of Brazil’s Terena indigenous tribe poses with a toy gun he has fashioned out of palm tree leaves on the disputed land where he lives with his family. A few days before, a member of the tribe was shot and killed during a police operation to remove them from the land they say is rightfully theirs. Pressed by a local investigator as to whom the gun is for, the young Terena boy says “The police. For when they come back.”

Earlier this year I spent some time with members of the Terena and Guarani-Kaiowá tribes in the Western state of Mato Grosso do Sul, where often violent clashes over land between indigenous groups, farmers, and armed pistoleiros are common. Photos below, click to enlarge.

After the death of Oziel Gabriel, the Terena tribe performed the bate-pau, or stick-beating, dance and musical ceremony, used traditionally to soothe the tensions of violence or war. A video of the beginning of the dance, which took place on land still contested by the tribe, local authorities and landowners, is here.

Laucir Marques was also shot during the police operation, and said he was left untreated for days at the hospital afterwards, because he was viewed by staff there as a rebellious Indian. Having spent time talking to both white and indigenous Brazilians near these conflict zones, this interpretation was not surprising to me, nor was it surprising to the local federal investigator. His video deposition describing the morning of the police operation is here.

A Terena tribe member in front of banana trees he has planted and cultivated on occupied land in Sidrolândia.

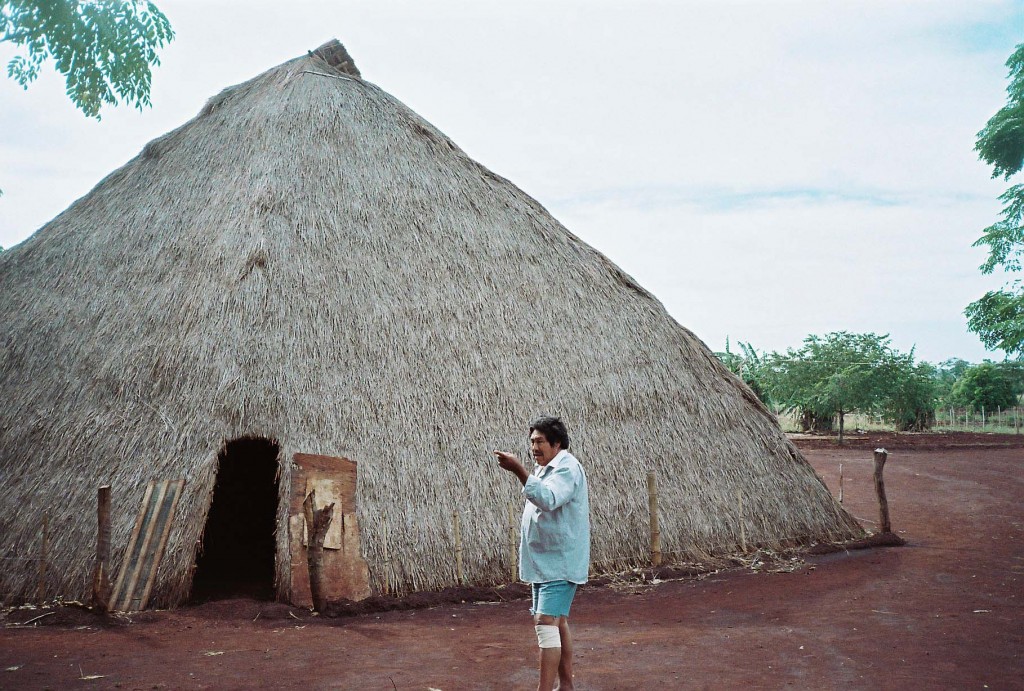

Further south in Mato Grosso do Sul, near to the city of Dourados, Guarani-Kaiowá member Getulio Juca Ava Potyvra, 60, stands in front of the village’s traditional “big house,” as it is referred to in Portuguese. Inside later with his wife, Alda Silva Kunha Tupa Rendyi, they show videos of old news clips about pistoleiro invasions and recall the many friends and relatives that have died in battles for land over the years.

Also near Dourados, Guarani-Kaiowá member Damiana Cavanha, 74, has lived here in this makeshift settlement alongside the highway for over 14 years. After being expelled from what she considers her rightful land, she has simply set up here, as close as legally possible to the farm, until she is allowed to return. The combination of shockingly high suicide rates and the chance of being hit by speeding cars mean the mortality rate of the Guarani-Kaiowá is far above the national average in Brazil.

On the contested land in Sidrolândia, Terena tribesmembers make their way home after the bate-pau ceremony. It’s easy to see why this land is so beloved.

Across Brazil, there are over 800,000 officially recognized indigenous peoples, and their way of life can take on radically different forms. There are still ‘undiscovered’ tribes in the Amazon who know little about the existence of ‘Brazil’ at all. And there are those, such as in the tribe pictured here, with post-graduate degrees and Facebook accounts, but that also may speak Terena at home.

Few things infuriate Terena chiefs more than the accusation, common around here, that they don’t “really live like Indians” anymore, and therefore don’t deserve special land demarcations. Their response (paraphrased from several interviews) is that it is racist, and absurd, to claim that everyone else in Brazil gets to adopt new technology and evolve but yet they must remain living in some “natural” state that exists in the European imagination. They aren’t just static parts of the landscape – they have history, just like white (or black) Brazilians. If Brazilians of Portuguese or Italian heritage develop a different way of life or manner of speech from their ancestors, no one would assume that means it’s OK for someone to come and steal their property from them. So why should it for native Brazilians?

The full story for which I took this trip is available here, for background.

During the bate-pau ceremony- “Indian warrior”

All photos Vincent Bevins