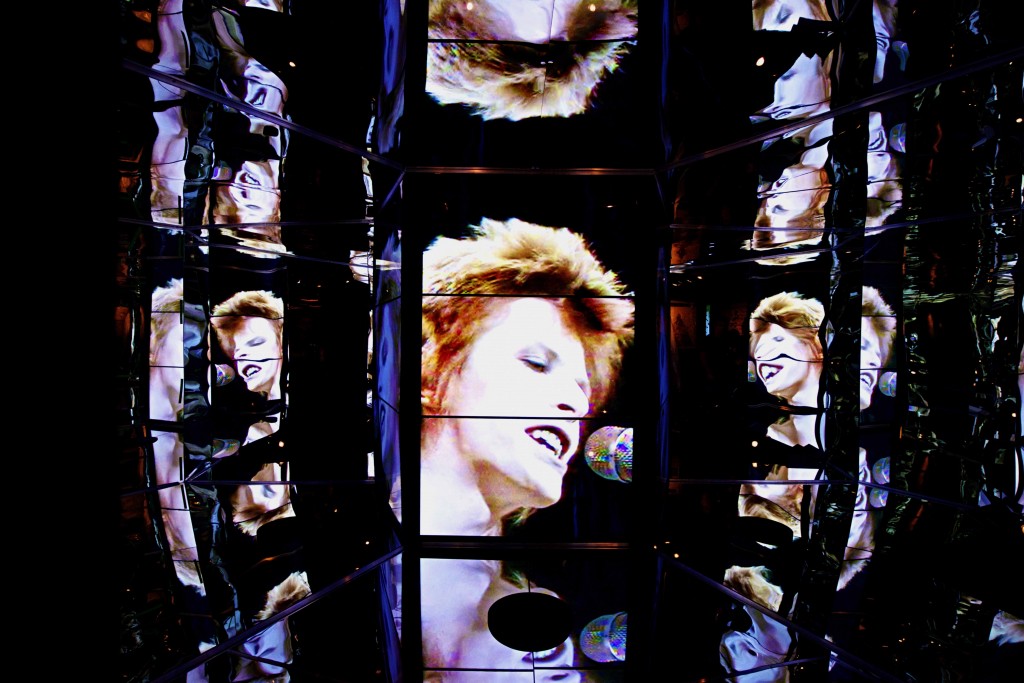

Alex Ellis took over as the British Ambassador here last July, having previously served as Ambassador to Portugal. Claire Rigby spoke with him last week following the opening of a major David Bowie exhibition at São Paulo’s MIS museum, which arrived in Brazil following showings in London and Toronto.

By Claire Rigby

Are you really a lifelong David Bowie fan?

Yes. The first music video I ever remember seeing was ‘Ashes to Ashes’. It must have been in 1980, and I remember being amazed. What’s this? I couldn’t work it out. It was like nothing I’d ever seen before. I think that’s quite a common reaction to seeing David Bowie for the first time, and you get that feeling again with some of the material in this exhibition.

How old were you then, and how old are you now?

I was 12 then, and I’m 46 now. Something that makes me respect Bowie even more after seeing this exhibition is that you realise the real depth to his work – it’s not an image: this is who he is. The clothes, the videos, the sheer creativity. These were some of the first people to make videos, some of the first people to use the internet.

Other than ‘Ashes to Ashes’, can you remember any other pivotal pop moments you had as a child?

[laughs] I think my parents may have occasionally worried. Lou Reed’s Transformer – I listened to that a lot about the same age. I certainly remember Beatles For Sale, the fourth Beatles album. I can probably still sing every word to every song on that. There were all the usual entry points to the pop of the time; and then The Jam, The Specials, Madness – the mods. 1979, 1980 – that’s when I really started getting into music.

How do you think that influenced you?

Well, to quote my wife, she says David Bowie has a very clear, strong identity, but a very hard one to define. She thinks that’s very British [Ellis’s wife is Portuguese] and maybe it is – it’s a funny combination. I think tolerance of eccentricity and of difference in Britain is something people often notice – the Brazilian ambassador once observed that to me. Another strong influence, I think, was the multi-ethnic nature of the music. Listening to The Specials, that was striking. It fostered assumptions that were very natural to me and people of my generation, which they weren’t to my parents’ generation. About the same time, I was going to see West Bromwich [football team], and they also had a huge diversity of players. It was how life was.

Is West Bromwich the team you support?

No, it’s Swindon Town – if you’re brought up in Wiltshire, there’s only one football league team and that’s Swindon Town.

What’s so specifically British about Bowie?

Britain is the second biggest exporter of music in the world, but manages to be both commercially successful and extraordinary – very avant-garde. In some cultures, the avant-garde is considered elitist, but there’s nothing elitist about David Bowie. Just listen to Gary Kemp [of Spandau Ballet] in the exhibition, talking about watching Bowie on telly and thinking, ‘This is for me.’ Bowie is accessible to a huge number of people, and he’s unafraid to roam around a lot of different areas and try different things. He’s also very global. His is a voice that really resonates in a country like Brazil: I was listening to Seu Jorge’s versions of Bowie songs – he recorded a whole album of them for the film The Life Aquatic, in 2005. If Seu Jorge is singing Bowie, you know he’s found his way into Brazilian culture.

The celebration and promotion of British culture, as with this exhibition, is key to the Foreign Office’s campaigns worldwide. What does it actually translate to for Britain?

Well, it attracts people to Britain, to put it bluntly. It’s so definably British. I think things like this exhibition show the nation’s creativity, and also its global nature: the director of the V&A museum [the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, where the Bowie exhibition was devised and first shown] is German. The governor of our Central Bank is Canadian. Britain draws people in and attracts talent from all over the world, and we also export it.

How do you think David Bowie might feel about being part of such a campaign?

I’ve no idea! I think one thing you can take away from a Bowie exhibition is that he does his own thing. But one of the other reasons I wanted to come along to this today was the V&A museum. Our museums are a very British mixture of the traditional and the very innovative. Three of the five most visited museums in the world are British, and many of them – the British Museum, for example – are global museums, telling a global story.

The UK government’s ‘Britain is Great’ campaign uses pop music extensively as part of its promotional material, but is pop a risky strategy for politicians? Musicians can be very transgressive – Bowie for instance. He was into so many different things and that’s clear in the exhibition: there’s a tiny cocaine spoon in it, for example, that belonged to him in the 1970s. Is his shocking, edgy nature made safe for use in government campaigns like these by time and distance?

Not necessarily. In Rock in Rio, we had Jessie J playing and Florence and the Machine, and they’re very much in the here and now.

But they’re not really transgressive performers.

I don’t know about that – watching a Valkyrie [lead singer Florence Welch] dancing in a light blue gown into a crowd of 200,000 Brazilians strikes me as pretty extraordinary. Like Bowie, she’s extraordinary, and people are interested in that. Brazilian tourists are very keen on our music events and festivals, and that’s growing fast – Brazilian tourism to the UK doubled in the last decade, though of course, they are also travelling more everywhere.

What’s the visa situation currently for Brazilians wishing to visit the UK?

You don’t need a visa if you are a tourist going from Brazil to the UK. If you are student you do, and then it gets into how long you’re staying and what you’re going to be doing, in the case of different kinds of visas.

There were a few problems last year, with some Brazilian tourists being turned away at the UK border.

Visa policy is something you constantly look at, and that’s driven by some publicly available numbers about over-stayers, high-risk individuals. That’s what causes it. From what I understand though, the number of over-stayers is dropping, which is good news. It’s one of those things one periodically looks at.

Why do you think the number of over-stayers might have fallen? Do you think some Brazilians might be returning to Brazil for economic reasons?

I couldn’t say. Perhaps it’s the result of more effective campaigns, and good work by the Home Office. But Brazil has very low migration both in and out, for a country that used to have such enormous migration numbers. There’s full employment here and for a lot of people, that has to be very attractive.

With the World Cup just 140 days away, what do you think are some of the challenges facing Brazil?

Well, Brazilians can explain that better than I can. It’s a big country and the World Cup will be in 12 different cities, which has never been the case before. That’s always going to present challenges. It’s probably under-visited for a country of its size – Brazil receives 6 million tourists a year, compared with 30 million to the UK. But it held the Confederations Cup last year, and the Pope’s visit, which brought a good few million people to Rio. I think they actually have a fair amount of experience.

Has the UK been sharing its experience and expertise on holding big events like these?

We’ve certainly worked with them, on everything from security through to fan fests. That sometimes means British firms with expertise: when you sit in your seat at the Itaquerão [the stadium being built in São Paulo, set to hold the opening match], your seat will have been designed by a British company – it’s the same company that did the Olympics. The excellent Sports Grounds Safety Authority, which was formed in 1989 after the publication of the Taylor Report [the results of the official inquiry into the Hillsborough football ground disaster in Liverpool in 1989, in which 96 people died] has been working with some of the grounds here about running safe events. And everything in between really. Brazilians are always interested in how other people do things.

What did the security aspect you mentioned consist of – did it also include policing?

Well, the Sports Grounds Safety Authority has done some work on security, and there have been UK commercial companies which sell security kit. We’ve certainly also had a lot of sessions around the country on security and how it works, hosted by the Brazilians, at their invitation. As we get closer to the event, there’ll be a lot more work on that. There’s a bit about policing, but a lot of it is about other stuff – stewarding, for example, and building design, and how to make that secure.

In terms of diplomacy, one of the aims of the British government is presumably to improve UK–Brazil relations. You’ve only been here a short while [six months], but how do you think that’s going – have there been improvements?

Well, what we’re here to do first and foremost is to promote British interests – the security and prosperity of the country, and also for the consular work we do. But yes, over the last four years the British government has made a long-term investment in emerging powers, of which Brazil is most certainly one, and we’ve seen a growth in exports, of Brazilian investment into the UK, and of British companies investing in Brazil. And we see a deeper relationship on the security side as well.

In what way can better relations with Brazil help promote British security?

It can happen in various ways: it can work on a global level, where you’re trying to get coalitions together on issues like the prevention of sexual violence in conflict, which is something the Foreign Secretary [William Hague] is very keen on. It can work in relation to the Falklands, which is British sovereign territory.

Where does Brazil fit in regarding the Falklands?

Because of its geographical proximity, basically. We’re trying to increase human relations between Brazil and the Falklands: anything that helps people to understand more about the Falklands and, more to the point, the islanders. We had the first visit by a Falkland Islands politician, who came to Brazil and went to three different states. We’re hoping the Falkland Islands cricket team is going to come to Brazil. We’ve had some staffers from the Brazilian Senate who have gone to the Falkland Islands. It’s important for the Falkland Islands because they sit in this region.

What’s the Brazilian position on the Falklands?

They are quite careful in what they say. They follow the regional position; but they listen to us, and we try and explain, and to build up the human links.

Regarding the NSA revelations that led to President Rousseff cancelling her state visit to the USA, were there also questions to be answered by the British government here in Brazil?

We’ve been talking to them for a long time about the world of internet governance and internet security. Freedom of expression, and things like that. It’s broader than just security. We work with them in a lot of different forms – the UN human rights council, the UN General Assembly. I was called in just after I arrived in Brazil because of the detention of David Miranda at Heathrow, and I spoke to the head of the Foreign Ministry about that.

What was your position?

That the law should take its course.

Were there further questions to be answered regarding the subsequent revelations about Brazil and the NSA?

No, I haven’t been asked back in to discuss those things.

You gave a speech on your first visit to São Paulo in which you talked about social changes in Brazil.

You can see it happening before your eyes. Economic change leads to social change, inevitably, and the great challenge for political systems the world over is how you adapt to social change. It’s true of any country, and not only of democracies. It’s happening in China, it’s happening in Turkey, and it’s happening in Brazil. All over the world, electorates are getting more demanding and they’re getting more impatient, and how you manage that is a tough thing to do, if you’re a government. People want better services quicker, and they’re not satisfied with being promised large sums of money – they want the reality of better services, quickly. Lula put it very well just after I arrived. He said that when he took over, the issues facing Brazil were inside the house. Now they’re outside the house. They’re no longer about whether you have a TV, but whether you can get to school. Whether you can get access to a doctor. Expectations have grown.

Finally, you were a history teacher before joining the Foreign Office. Since then you’ve been involved in a number of historic events, from the creation of the euro and the 2004 expansion of the EU to the period you spent in South Africa, following Mandela’s release. In your diplomatic career so far, what has been the most historic event for you personally?

It’s a real privilege in my work that you get these kinds of opportunities. But I think if England win the World Cup here in Brazil, that would take the biscuit.