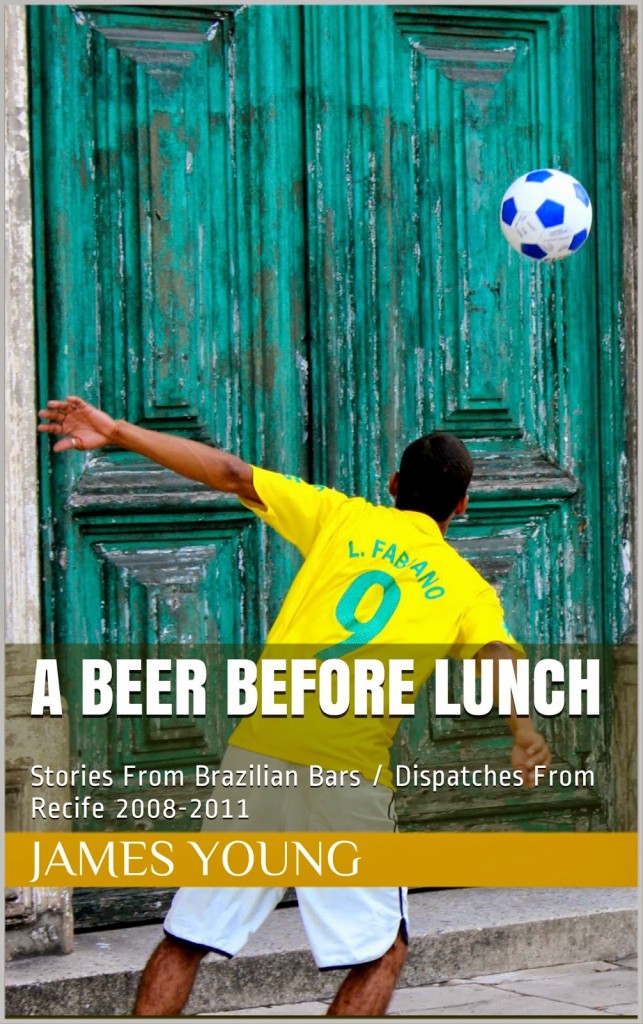

Nathan Walters asks why so few foreigners recently have chosen to capture Brazil in letters, and takes us through the rare exceptions that open up the country to international readers. Above, the cover of a recently published book by From Brazil contributor James Young.

Nathan Walters

So much of Brazil’s literary treasures remain locked in the Portuguese language, which is a shame for the world. Though some of the country’s iconic authors, like Clarice Lispector, Machado de Assis, Paulo Coelho and Jorge Armado, have been competently translated, so much remains reserved for those at or nearing fluency.

No translation can compare with work in the original language, and that’s most definitely the case with Brazilian Portuguese. Brazilians love wordplay, and their language is full of idiomatic expressions that are largely untranslatable. Brazilian novels that rely heavily on slang might be pure poetry in the native tongue, but tend to fall flat when translated to another (Paulo Lins’ City of God is one example). The situation can be frustrating for foreigners who want to learn more about Brazilian culture.

Though quality nonfiction works about the country by foreign writers are easy to find (Joseph Page’s The Brazilians, Michael Reid’s Brazil: The Troubled Rise of a Global Power, and Larry Rohter’s Brazil on the Rise stand out), fiction works by foreign authors that tap into the seemingly endless possibilities Brazil offers remain rare.

We have to ask why. Because to anyone with even the slightest inclination to write, Brazil is a paradise.

The streets in the major cities, like Rio and São Paulo, are littered with spectacular histories. And the vast interior, replete with realities that would make Zola blush, remains largely untouched by the imaginative storytelling of foreigners.

The country’s history is sprinkled with some amazing stories of foreign writers that have made a splash here. Austrian Stefan Zweig’s Brazil, Land of the Future may best be remembered for its misappropriation: “Brazil, land of the future…and it always will be.” Hungarian Paulo Rónai fell madly in love with the country and the language in the early 20th century. French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss spent months trekking through the unwieldy Amazon. Hunter S. Thompson used to work with his Olympia SF typewriter out on Copacabana beach.

Yet, few Anglophone writers enjoy the prestige reserved for American poet Elizabeth Bishop. While Bishop’s autobiographical poetry manages to capture the complex feelings of a foreigner’s life in Brazil, the form leaves fans of literary prose wanting.

In the early 1990s, American novelist John Updike spent time in the country for his novel Brazil. Though considered a bit cliché, the work remains one of the few where a foreign author takes on the intricacies of the whole country, the regional idiosyncrasies, and the social issues that continue dominate public discourse. Imaginative, well written, sexualized (it’s Updike), the novel remains a notable work of fiction dealing with the splendor and anguish of life in Brazil.

Brazil was published in 1994 and in the twenty years since, Brazil has opened its doors to foreigners, who now pour into the country in droves. Yet, the flow of fictional works from expat writers has failed to keep pace.

There are many explanations for this. For one, weaving a story into the complexities of Brazil is no easy task for foreigners who are still doing their best to understand the country.

Sarah de Sainte Croix, an English writer living in Rio for the past four years, has organized a writers group in Rio (Rio Writers’ Forum), one of the few support networks for foreign writers in the country, where foreign and native writers gather to share their experiences and work during weekly sessions.

“One difficulty we have talked about in the group is not knowing where to set our stories. As we are mostly foreigners, it can feel like we are impostors if we write Brazilian stories, and yet many of us feel quite detached from our countries of origin and the details of everyday life there,” she says. “One solution for our Brazilian stories is to create ‘foreign’ characters to tell them. The other is to simply bluster ahead and invent, despite our insecurities, and in the name of fiction. Which is actually quite a good metaphor for moving to another country when you think about it, because most of the time it feels like you’re living inside a big, unwieldy story, with surprises around every corner, making it all up as you go along.”

Author James Young, author of A Beer Before Lunch, a collection of stories set in Recife, as well as From Brazil contributor, has been writing in Brazil for years, but still faces the challenges most expat writers deal with.

“I think there are two challenges for an expat writer living in Brazil. One is the need to be original and avoid stereotype and cliché,” Young says. “I think there’s a cycle to most expat lives here—the initial giddy honeymoon phase, the plateau that comes when real life kicks in, the discontent as frustrations seem to outweigh benefits, and then hopefully, a return to the plateau and a realization that there are good and bad things about life anywhere. No one should ever write anything during the giddy honeymoon phase!”

Another problem is the fact prose fiction has taken a backseat to other forms of enjoyment (Why read a novel when you can watch a video of a dancing cat?).

James Scudamore, the British author of the 2009 novel Heliopolis, has won accolades for his story of life in modern São Paulo, but to finish the novel (one of three by the author) he had to face down the same obstacles every writer faces.

“The usual ones, especially persuading myself to keep on doing it in the face of my own laziness and the basic indifference of much of society towards prose fiction. But once the urge to do it has been implanted, you can’t ignore it. Or rather it won’t ignore you. It’s a compulsion.”

For Scudamore, the urge to write about the concrete jungle that is contemporary São Paulo was implanted as a child during a temporary residency in the city, one of many homes during a childhood shuttling around the globe.

“I think the idea that I might try to write fiction probably first came to me when living in Brazil. It’s certainly the earliest memory I have of trying to write stories. Something about piranhas, when I was 9. But I think more widely the fact of having been moved around so much as a kid was a key driving factor: abrupt rupture and profound change are often to be found in the childhoods of those who end up writing fiction. It leaves you with a sort of ‘yearning energy’- an urge to recreate in prose the places you are missing in real life. The act of missing things becomes an act of invention.”

For those inclined to face down the challenges, Brazil is fertile ground for fictional creations.

“Brazil is a tremendously evocative country, entirely removed from drizzly Belfast where I was born. It provides a vivid backdrop to any story—whether it’s the light, the smells, the sounds or the people,” says Young. “Moving to a country like Brazil can be an almost hallucinogenic experience—it allowed me to escape the confines of my other life and look at things in a fresh way.”

For some expats, writing in Portuguese for a Brazilian audience is now more interesting than weaving stories in their native language.

American writer Julia Michaels, perhaps the most well-known gringa blogger in Brazil, has lived in the country for more than thirty years. After a few attempts at writing a novel, Michaels says she gave up to focus on other writing projects.

Her 2013 memoir Solteira no Rio de Janeiro was well received by Brazilian audiences, but the English edition is still in the works.

“I’m lucky to be able to write in Portuguese and direct myself to Brazilians, this is a great relief. Otherwise I would be very frustrated because books don’t sell. It’s a tough career!”

Pelas Entreviagens, the 2014 travelogue from New Orleans transplant Heyesiof Epwe’ru is an account of the writer’s time working as a translator in Bahia. So much of Epwe’ru’s story, the expressions, places, commands the Portuguese language, so why fight it?

Perhaps not surprisingly considering the attention given by local writers, many stories set in the country explore the two major themes that dominate the outside world’s vision of Brazil: violence and inequality.

“Rather sadly, the one narrative strand that underlies much of my work, and pops up again and again, involves the poverty, violence and tragedy that results from the inequality that so scars the country,” says Young. Echoing the sentiment of other expat writers. “Such inequality exists everywhere of course, but not on the scale that it does here. The size of everything in Brazil—the country itself, the cities, the crime rates, the incredible numbers of people—feed my imagination.”