Political and social engagement has been a dominant theme at this year’s São Paulo Bienal. Claire Rigby on participating British artist John Barker, who was a member of an armed urban guerrilla group in the UK in the 1970s.

By Claire Rigby

As the São Paulo Bienal draws to a close this Sunday, and visitors hurry for a last-chance look at the sprawling exhibition, a series of images comes to mind again and again, foreshadowing some of the artworks that will be most vividly remembered, perhaps, when the 31st Bienal is far away in the distant past.

It’s hard to imagine Éder Oliveira’s immense, haunting portraits being easily forgotten; or the sight of Yael Bartana’s Templo de Salomão, crumbling to dust as São Paulo stands, impassive, around it.

[Esta matéria foi publicada hoje na Folha. Para ler em Português, clique aqui]

Profoundly memorable too, with its surreally powerful images and simmering radical chic, a collection of posters by the Austrian/British duo Ines Doujak and John Barker, part of the installation ‘Loomshuttles/Warpaths’, has lingered in the mind of many a visitor, crystallising, with their insolence and visual impact, many of the 31st Bienal’s most pressing concerns – colonialism and imperialism, rebellion and resistance.

A papier mâché sculpture, Haute Couture 04 Transport (see image below), depicts a German Shepherd dog penetrating the late Bolivian labour leader and feminist, Domitila Barrios de Chúngara, who is doing the same in turn to a queasy-looking Juan Carlos I. The former King of Spain spews cornflowers onto a bed of German SS officers’ helmets, rotten and crumbling with age. “It’s a visceral representation of forms of exploitation,” the artists told Folha de S.Paulo. “It plays with and subverts relations of power”. It does, it’s safe to say, do that. A wall and an advisory notice were added to the installation in October, to hide the sculpture from the eyes of under-18 visitors to the Bienal.

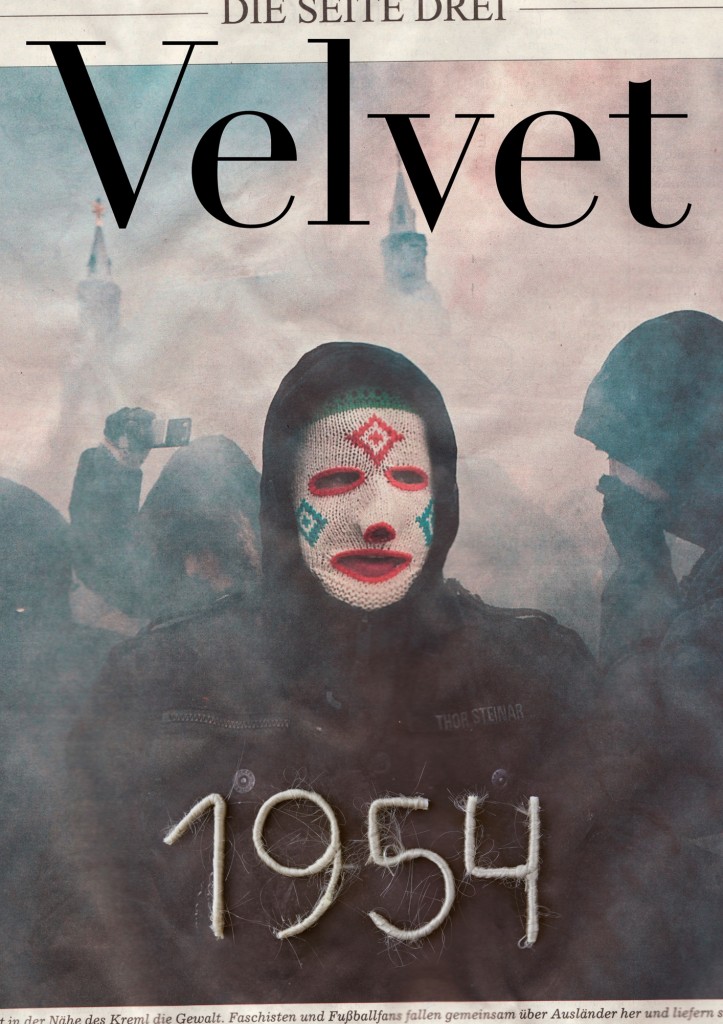

Two bowler-hatted altiplano women stare out combatively in the poster ’Twill’, while ‘Velvet’ (above) depicts an insurrectionary figure swathed in teargas, wearing a knitted Peruvian ukuku balaclava – South America’s very own, original Anonymous-style face mask. Another poster, one of two to have been made in Brazil as part of Doujak and Barker’s residency here, shows a masked MTST activist in front of the Prefeitura de São Paulo.

Insurgency hangs in the air; and for one of the artists involved in ‘Loomshuttles/Warpaths’, it reaches deep into the past too.

The angry years

A a young man in London in the 1970s, John Barker, now 66, was a member of the Angry Brigade – an armed libertarian communist group that carried out at least 19 bombings and six attempted bombings between 1970 and 1971. Their targets included police stations, a Territorial Army Centre, the homes of government ministers, and the Spanish embassy, which they strafed with machine-gun fire in December 1970. They bombed the Ford motor car factory and the home of the company’s chairman, a number of banks, and a BBC vehicle covering the 1970 Miss World pageant.

They even bombed the Biba boutique on Kensington High Street, at the heart of ‘swinging London’. “If you’re not busy being born, you’re busy buying,” reads an Angry Brigade communiqué issued after the attack. “Brothers and Sisters, what are your real desires? You can’t reform profit capitalism and inhumanity. Just kick it till it breaks.”

Britain in the early 1970s was seething with political unrest, protests and strikes, under the Conservative government of Prime Minister Edward Heath. The Angry Brigade hoped to help escalate that tension by the use of spectacular, revolutionary violence. Writing in the Preface to Gordon Carr’s book The Angry Brigade: A History of Britain’s First Urban Guerrilla Group, Stuart Christie, an alleged member of the group who was nevertheless acquitted at trial, wrote, “their methods – effective or ineffective, rightly or wrongly – did give voice to a social conscience, and expression to an important libertarian impulse at a time when it felt that huge social change was still possible.”

On 12 January 1971, a demonstration against the Industrial Relations Act, which aimed to restrict the influence of Britain’s powerful unions, brought thousands onto the streets of London in protest. That night, the Angry Brigade set off two bombs at the home of Robert Carr, the Secretary of State for Employment. The Carr bombing brought the might of Scotland Yard down upon the group in an investigation that led to the formation of the Bomb Squad, now known as the Counter-Terrorism Command.

The reckoning

The Angry Brigade’s plans started to unravel when a scam involving fraudulent cheques, used to fund their activities, was uncovered, leading to the arrest and trial of two alleged Angry Brigade members in early 1971. In August that year, John Barker and seven other people were arrested in London, and charged with “conspiring to cause explosions likely to endanger life or cause serious injury to property”. Evidence presented against the Angry Brigade at the Old Bailey, London’s highest criminal court, included gelignite and detonators, guns and ammunition, as well as the printing press used to produce many of the communiqués issued by the group.

In December 1972, after a six-month trial, Greenfield, Barker, Anna Mendelssohn and Hilary Crick were found guilty and sentenced to ten years each, classified as Category A prisoners – a threat to national security. “In my case, they framed a guilty man,” Barker wrote of his conviction in his 2006 prison memoir, Bending the Bars. Barker served a further prison sentence in the 1990s, convicted for his part in a major cannabis smuggling operation.

Happy to answer questions, with Ines Doujak, about the Bienal artworks themselves, Barker preferred not to be interviewed on the subject of his radical past in relation to ‘Loomshuttles/Warpaths’, writing in an email to Folha, “The work does, and needs to, stand on its own merits”.

Barker nevertheless spoke about the angry years in an interview he gave to the Guardian in June 2014, on the publication of his novel Futures, a crime story in which the cocaine trade is the pivot linking the fates of a cast of London characters.

He looks back on his years in the Angry Brigade, he told the Guardian, with “critical respect” for their commitment and their anger – “which I still feel, and probably even more so”. Regarding the decision to take up arms, Barker told the East End Review, also in June, “It’s not a moral question is it? It’s, you know, did it do anything strategic? I’m totally against terrorism as I understand it, which is indiscriminate killing. Obviously you don’t want to hurt people.”

Like the USA’s Weathermen, but in contrast with Germany’s Baader Meinhof Gang/Red Army Faction, and the Italian Red Brigades, thought to have been responsible for 34 deaths and close to 50 deaths respectively, the Angry Brigade took care to avoid causing injury to people. Only one person was harmed as a result of its bombing campaign: Elizabeth Wilson, the housekeeper of a neighbour of John Davies, the government minister for Trade and Industry. Wilson stepped into the hall moments before the bomb, disguised as a gift for Davies, exploded, injuring her legs.

It was a miracle, said a forensics expert, speaking at the Angry Brigade trial, that nobody was killed or seriously injured as a result of the group’s bombing campaign. “Mr Yallop, would you tell the court what is the statistical probability”, asked Anna Mendelssohn, representing herself at the trial, as did Barker and Crick, “for there to exist an associated set of 27 miracles?”

The São Paulo Bienal

Visiting ‘Loomshuttles/Warpaths’ with curator Charles Esche in the penultimate week of the Bienal, we asked how Doujak and Barker had come to take part. The work Ines Doujak has been producing over the last decade or more was a good fit with many of the curatorial collective’s concerns, says Esche – “that is, relations between the coloniser and colonised; between indigenous and colonial cultures.”

Were the curators aware of John Barker’s past when the invitation to take part was issued? “We didn’t know about him until we learned of his work as Ines’s partner in ‘Loomshuttles/Warpaths’, but it did become apparent then,” says Esche. Did it matter? “I don’t believe it needs to ‘matter’ in any concrete sense,” says Esche. “Should there be a consequence for the fact that he served time in jail for actions he carried out 40 years ago?” Esche mentions President Rousseff, who when she was arrested in January 1970 on the Rua Augusta, was armed. “Does it matter that Dilma took up arms in the context of the military dictatorship?” He mentions Menachem Begin, the former Irgun militant against British rule in Palestine, who became prime minister of Israel in 1977.

Esche also mentions Gerry Adams, an alleged former IRA leader and the president of the Northern Irish political party, Sinn Féin, which first emerged as the political wing of the Provisional IRA. For the Angry Brigade, although it had no direct connection with the Irish Republican movement, one of the triggers for its campaign of violence was the Troubles, the armed conflict that gripped Northern Ireland from 1968 to 1998.

In August 1971, the British Army arrested 342 civilians in Northern Ireland, imprisoning them without trial in an act that sparked widespread outrage. The Angry Brigade’s response to the mass internment was to bomb the Territorial Army Centre in Holloway, in what was to be the group’s final attack before its members were arrested.

Armed and dangerous as they were, the Angry Brigade were small fry compared to the real wave of violence and bombing about to be unleashed in the UK, as the IRA bombing campaign, which had begun in 1968, got underway in earnest in the early 1970s. By the time of the Peace Process in 1994, the IRA had killed more than 1,700 people, including 644 civilians.

“The Angry Brigade actions,” Barker has written, took place “before the IRA made bombing a serious business.” In 1973, an IRA bomb exploded at the Old Bailey. “I was in [Wormwood Scrubs prison] when the Old Bailey bomb went off,” wrote Barker, in a review of an Angry Brigade history, Anarchy in the UK. “The whole jail celebrated, and I was relieved I’d already got my sentence. Bombing had got a lot heavier, and we’d have got heavier sentences.”

Follow @claire_rigby on Twitter